But today’s entrepreneur is as likely to be working in the nonprofit sector as well, applying the same creative spirit and high energy needed to identify a public need and start a business to the challenges of solving social problems by overcoming formidable obstacles to start-up a charitable organization.

Whether in the for- or non-profit sectors, entrepreneurs share several traits in common. They are self-motivated, relying on their own talents, passion and knowledge to achieve success. They are determined, with the ability to envision a start-up and to recover quickly from setbacks. They share the same essential qualities of great leadership, problem-solving and management skills, and team-building style. And being in the right place at the right time, with not a small measure of luck, often contribute to their successes.

Your Part-Time Controller salutes the many social entrepreneurs in our midst whose desires to improve and transform social, environmental, educational and economic conditions have helped make the nonprofit sector such a vibrant, dynamic and significant part of society. These leaders refuse to accept the status quo. They develop innovative solutions to local and global problems that set high standards for the entire sector and enable communities to enact meaningful change.

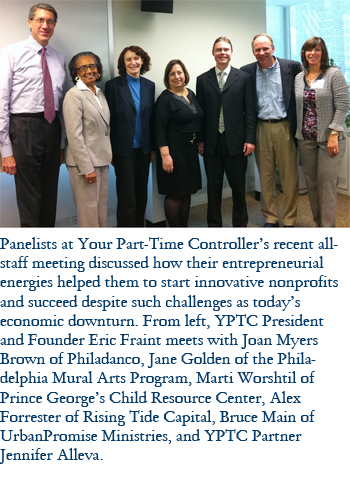

To share these leaders’ inspirational stories, we brought together a distinguished panel of five nonprofit founders recently as part of our ongoing staff training. Hearing how they got started, overcame obstacles, and succeeded despite great adversities, we feel, will inspire our staff to better understand our nonprofit clients and see opportunities for these agencies to succeed in their missions.

A common theme in the successes of all of these nonprofit leaders is the ability to not only survive, but thrive despite economic downturns. According to the panelists — who represented a wide array of current and former YPTC clients from the arts to social service organizations — securing scarce funding remains their biggest challenge given the poor economy.

Ask Joan Myers Brown what the biggest challenge to running a nonprofit is these days, and her answer is simple: “It’s called M-O-N-E-Y.”

Brown would know. The highly accomplished professional dancer is founder and executive artistic director of the Philadelphia Dance Co., known internationally as Philadanco, a West Philadelphia-based organization that promotes the African-American dance tradition.

As Jane Golden, founder and executive director of Philadelphia’s Mural Arts Program, noted, more and more nonprofits are chasing a pot of money that’s been diminished because of cuts in government funding.

The entrepreneurial nonprofit leader continually searches for alternatives and creative solutions to problems such as these. For example, Golden is trying to diversify Mural Arts’ funding sources by bringing in earned income from innovative initiatives like guided trolley tours of murals.

Dr. Bruce Main has a unique challenge as the president of a Camden-based organization that derives 90% of its funding from private sources. Main’s UrbanPromise Ministries, established in 1993, runs summer schools, summer camps and job training initiatives for low-income youths. Though government budget cuts have had little effect on his organization, he has had to learn how to navigate the “intensely relational” landscape of raising money through private donors. Potential donors, he says, are more willing to fund projects when they know and trust the organization’s managers.

Some panelists noted that their specific fields of interest are particularly hard to fund. Brown, for instance, said that benefactors of the arts are usually more reluctant to give money to dance than, say, classical music ensembles.

And Marti Worshtil, founder and executive director of Prince George’s Child Resource Center, said it was initially difficult to get funding for her organization because it serves a county that’s viewed as “the ugly step-sister” to Washington, D.C.

In other words, before Worshtil could convince donors to support her organization, which offers child development services, she had to surmount the inexplicably poor reputation of suburban Prince George’s County among the philanthropic community.

Another ongoing challenge faced by nonprofit organizations is the need to establish a functional, effective accounting and financial management system. Successful entrepreneurs learn when it is best to tackle a problem internally and when it’s more effective to find an outsourced solution. The panelists made clear that YPTC was particularly good in helping them to achieve success in this critical area of their operations.

Golden noted that “we were putting our checks in shoe boxes” when her organization started out.

Brown agreed. A previous employee in charge of Philadanco’s books was actually taking money unbeknownst to management in what Brown called a “train robbery.” YPTC came in and helped stabilize the organization’s finances and deal with tax problems caused by the employee.

And while the scarcity of funding was important for all five of the panelists’ nonprofits, Alex Forrester, co-founder and chief operations officer of Rising Tide Capital, asked to be freed of “the shackle of restricted funding.”

Forrester, whose North Jersey-based organization provides business consulting to low- and moderate-income entrepreneurs, said he refuses most restricted funding and instead searches for donors who are willing to support his nonprofit’s general operating budget. That type of funding allows Rising Tide Capital to focus on delivering programs that he and his employees think will be most effective.

Furthermore, Forrester said that YPTC plays a crucial role in keeping track of the disbursement of both restricted and non-restricted funds as well as cash forecasting.

Another common entrepreneurial challenge is the ability to grow a company or an organization and not spread oneself too thin – or to dilute its core message. Forrester is also concerned about “scaling the heart” of his enterprise as he grows it out of its beginnings in Jersey City to serve a larger area. He hopes to help establish similar organizations in different parts of the globe.

While Forrester said he wants to help a growing number of people, he also struggles to strike a fine balance so that Rising Tide doesn’t morph away from the “labor of love” that energizes it.

This concern was echoed by several other panelists. Main, for instance, was deluged with requests for help and time after UrbanPromise Ministries was featured on the 20/20 television newsmagazine.

Golden similarly spoke of the “ever-present angst” that rapid expansion causes her — Mural Arts now employs 300 artists and is responsible for thousands of works of art that the organization wants to maintain in perpetuity.

Yet despite these challenges, these panelists saw deep meaning in what they do – a mission and a passion that fuel the entrepreneurial spirit.

Main told the story of a young child who he found “curled up” in a 76ers sweatshirt on the stoop of the church where he was working. Though that child ended up getting sent to prison for a murder, he was recently released and Main is hopeful he can put his life back together. Main has made it his mission to stop the cycle of children like this one “going to jail rather than going to college.”

As Forrester put it, for these panelists “the purpose of life is to learn how to love.” And his nonprofit is the way he demonstrates that love.